In this article:

- What do the dogs at Working Dogs for Conservation do?

- How do I decide when to retire my working dog?

- How can I make sure my dog is happy in their retirement?

- How can I re-center my attention on a retired dog?

According to the conservationists who worked alongside him, Tobias is a “legend.” He distinguished himself for years among his colleagues as indefatigable in his pursuit of invasive and endangered species. He was a hard worker with tremendous focus, but also had a sense of humor that made him a joy to be around. Sadly, when Tobias began to suffer from a degenerative spine condition, the decision had to be made: It was time for him to retire. Nobody could really tell him that though. Not because he didn’t want to hear it, exactly, but because Tobias is a dog.

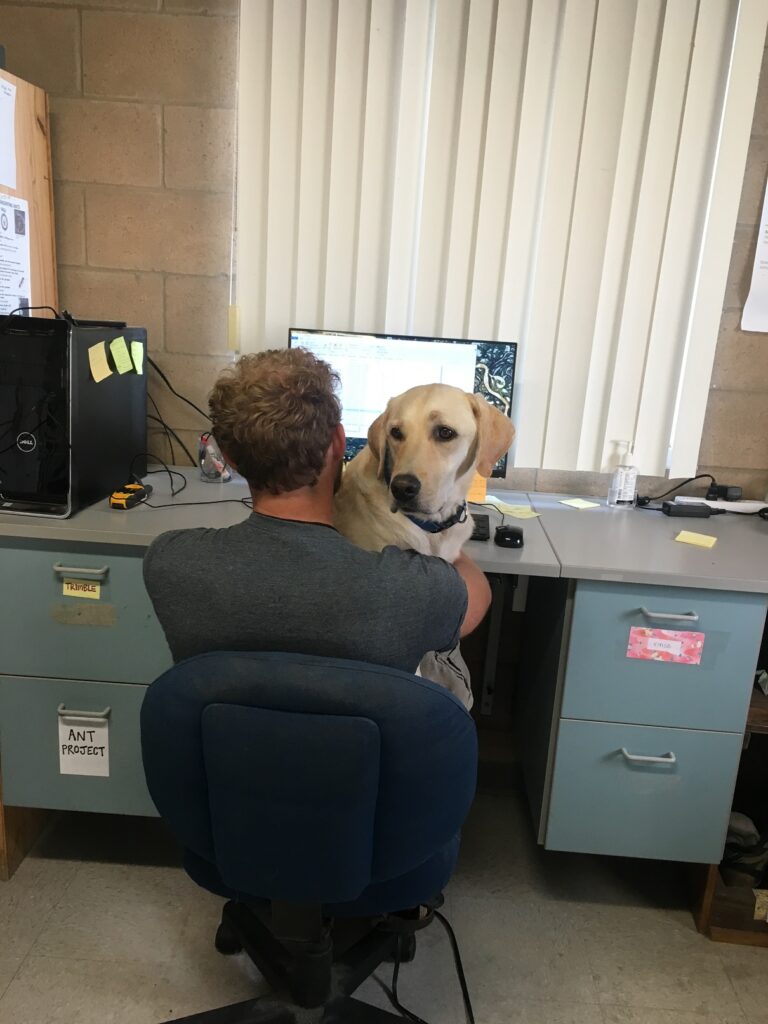

The yellow Lab is employed by Working Dogs for Conservation (WD4C), a Montana-based nonprofit that rescues dogs from shelters, rehoming situations, and careers that aren’t a good fit. Their team trains the dogs, then deploys them on conservation projects around the world. WD4C has about twenty active dogs on its roster. Even those who are retired like Tobias are considered active because of WD4C’s Dog Life program, which ensures the dogs remain a part of the organization for their entire lives (more on the Dog Life program later).

Tobias’s career makes him different from most family dogs, but he still has a lot to teach us about how to keep any dog happy as they age and change—and maybe how to retire as a human as well.

Scent-work champ, sweetie, and “world-class shedder”

Tobias was a stray in Helena, Montana, before landing in the Carroll College Anthrozoology program, where students regularly train dogs for service work. Though he seemed goofy and easygoing, the students could tell he had an extraordinary brain that was suited to conservation work, and connected him with WD4C to start his career.

One of the humans who knows Tobias best is Ngaio Richards, PhD and WD4C forensics and field specialist. Richards is not Tobias’s primary handler, but considers herself more of an “auntie” and colleague, having served alongside as his handler on several projects over many years. The time the organization’s humans and canines spend training, traveling, and on active jobs together creates a deeply bonded team, whether the humans are the “owner” of a particular dog or not, she said.

Each dog is trained on various scents across their career, and Tobias excelled at sniffing out blunt-nose leopard lizard scat and dyer’s woad with Richards, among several other targets he sought with other handlers. What stood out to his handlers, though, was his ability to actually “chill” in his off hours. Richards said this is unusual for the types of dogs who make great conservation workers. She joked that they are, in a word, “bonkers.”

Tobias is that, too—but mostly he’s a goof. He makes a game of his personal gaseousness with his handlers. “Many is the time I have succumbed to the lure of bending down to greet him,” Richards said, “only to have him belch joyously in my face, then scamper off obviously delighted with himself.”

No surface is safe from his blonde hair, which he sheds at “Olympic” levels. He loves toys—all the dogs in WD4C are rewarded with play rather than treats—and goes nuts for stuffed animals, as evidenced by this photograph of the “toy hoarder”:

Deciding when to retire a working dog is rarely easy

Tobias is a dog with a ton of personality and skill, whose working career ended before WD4C—and probably he—would have liked. He was recently diagnosed with intervertebral disc disease (IVDD). This degenerative condition impacts the spine, and, while treatable with surgery and lifestyle changes, rules out certain types of physical work.

The moment when any dog must retire is never exactly the same, and Richards described the first hints that the transition is around the corner as a feeling more than a firm checklist. Minor injuries might take longer to heal. She might spot a subtle slowing down. Or, even less concrete, she feels their time together during work is suddenly “different.”

There are a few signs that would indicate a dog’s retirement time has come.

- Physical health changes: Conditions like arthritis, IVDD, or other musculoskeletal and neurologic issues can make physically demanding work painful or unsafe, even if the dog is still mentally eager.

- Mental health shifts: Older dogs may develop cognitive changes that make complex tasks harder, even if they still enjoy familiar routines.

- Behavior and stress: More subtle signs, like increased restlessness, reluctance to work, or changes in enthusiasm, can be early signals that a dog needs a lighter load or a full stop.

For their human colleagues, these changes can be devastating.

“When you’re out there in the field and you’ve just wrapped up your last-ever survey together, I want to say, you know, it’s trumpets, confetti. But it’s hard for me not to feel a huge amount of sadness and loss and grief, to be perfectly honest,” Richards said.

Still, while Tobias’s body is no longer up to a full workload, his mind —and silliness—keep on keeping on, and the people around him made sure his retirement plan recognized that.

What Tobias teaches us about “good retirement”

For dogs like Tobias, retirement isn’t about catching up on your daytime soaps from the couch. These dogs have spent years in jobs that tap into their personalities and instincts: sniffing, searching, problem-solving, and working side‑by‑side with their humans. A good retirement lets them keep that up to the extent their abilities will allow.

Through the Dog Life program, which is how WD4C plans for and organizes care for their working dogs after their careers come to an end, the team treats retirement as a carefully planned transition, not an on‑off switch—shifting dogs to lower‑impact projects and spacing out trips. The goal is to create a path that honors the dog’s body and drive. It also ensures that the primary owners of the dogs, and all the dog’s former colleagues, don’t manage a dog’s retirement alone.

“The Dog Life program,” Richards said, “is obviously crucial for the dogs, but it’s also crucial for the handlers. We have to make an adjustment after having spent some of the best moments of our whole entire lives out looking for targets, just being with these dogs.”

Tobias’s different day-to-day offers a lot to recommend the Dog Life program. He still gets to “work” through ride‑alongs: traveling to familiar survey sites, putting on his vest, sniffing, and then getting back into the vehicle when his body has had enough. One thing that has not changed, according to Richards, is that at the hotel, Tobias turns the room into his own private comedy club, scooping up armfuls of toys onto his bed and demanding encore after encore of fetch.

A few things stand out in how Tobias’s team cares for him that may be useful in any working dog’s retirement, and any companion dog’s senior years.

Build in quality time

When a WD4C retires a dog, the handler’s job becomes, in part, just spending time with them. Richards acknowledges that her role, which builds into the job description this imperative to simply hang with dogs when they’re done working, is unusual.

But more quality time is something anyone can attempt to offer a retired dog. Since they won’t be naturally spending time on the job, be intentional about spending more time with them.

This goes for your pet dog if they can’t fetch, run, or play a sport like they used to—they still need your companionship and love.

Gradually wind down, but continue meaningful work

Even for Tobias, who has a physical need to retire, WD4C winds down gradually. They keep Tobias’s brain busy, even as his body slows down, by doing very similar work to what he did before—ride-alongs and small “jobs” that let him use his nose without putting too much strain on his spine. Its work that has been historically meaningful for him.

For other dogs, this could mean lowering the physical impact of the work while keeping their routine: Shorten hikes or keep terrain more level than before. Trade stairs for ramps. Teach them new nose‑work games in the yard or living room.

Do keep a “job” on the calendar: Simple tasks like sniff‑walks at a regular time, or low‑impact training, can help to keep up a routine—and keep their lives fun and interesting. After all, dogs, just like their human counterparts, can get bored.

Add useful tools to the repertoire

Even as WD4C adapts Tobias’s environment to be safer for a dog with IVDD and winds down his work, they add in tools. For example, some days he gets hydrotherapy. The team is also had him fitted to a cart, which helps him go for longer walks despite his spinal issues—because he still clearly wants to.

Work with your dog’s veterinarian to find the most beneficial tools that will help keep them active.

Share the load

WD4C is special in that they have a built-in community that shares the responsibility for retired dogs. Though dogs like Tobias live with one person when they retire, a dedicated Dog Life group meets regularly to talk through each dog’s needs, from work assignments to retirement plans and, eventually, end‑of‑life care. There’s a built-in support group for the handlers-cum-caregivers. No one person carries those decisions alone.

You, too, can build a little village. Your own version could include a trusted pet-sitter, friends and neighbors who know your dog, a great vet, or a favorite trainer. They can make the emotional weight of retirement and, eventually, loss much more bearable, allowing you more mental space to enjoy your time with your dog and ensure their life continues to be the best one possible.

Tobias: Same, but different

For a dog whose life has been about purposeful partnership, being surrounded by people who adore every side of Tobias—the worker, the cheese ball, and even the shedder—may be the most meaningful retirement benefit of all.

For any dog—whether they’re a high-octane conservation dog or simply an active best friend—Tobias’s new life can show the way to a good retirement: remaining seen, engaged, and deeply, joyfully in the middle of their peoples’ lives for as long as possible.

When a dog ages out of their work, has to retire due to illness or injury, or can no longer participate in certain favorite activities, their lives and your relationship will change. But you’re not losing them. These changes can be an opportunity to re-center your attention on them, learn what they need and love now, and provide it for them.